A major new report released today by the International Energy Agency (IEA) outlines its vision of a pathway towards net zero emissions by the year 2050, highlighting the broad, significant effort required to achieve the goal but also the feasibility of several key actions.

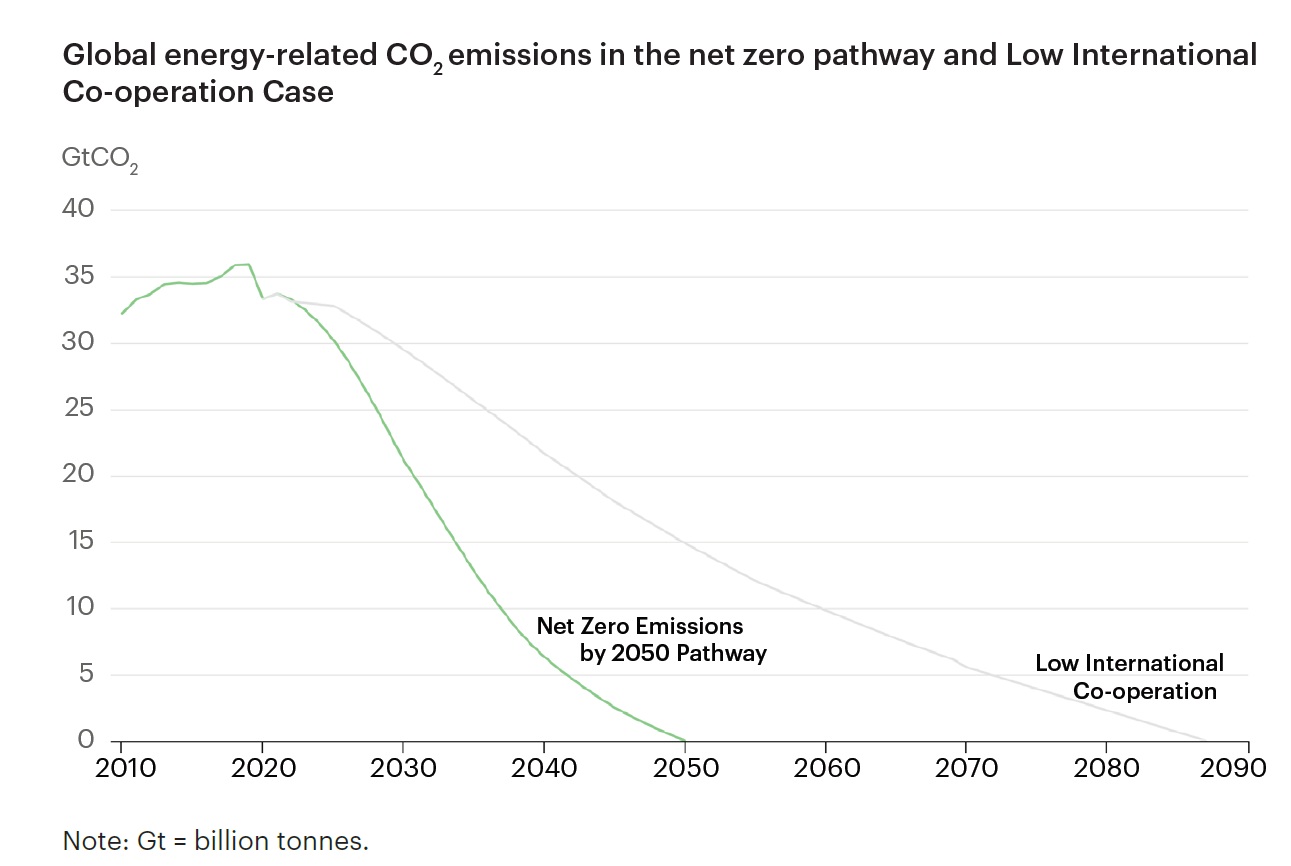

The report focuses on the energy sector, around three quarters of total global CO2 emissions. The report shows that while 70% of the world’s emissions fall under countries that have pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2050, but that those pledge are not underpinned by near-term policies and measures. Even if these pledges were fulfilled, global temperatures would still exceed 2.1 degrees Celsius by 2100, and post-COVID19 recovery policies that are fossil-heavy are due to almost certainly cause a massive rebound in global emissions over the coming months and years.

Actions to keep net zero by 2050 within reach include boosting the deployment of existing technologies in the short term, investing in future research, focusing on behavioural changes and enhancing international cooperation.

The report calls for a wide range of actions that are explicitly or implicitly opposed by Australia’s government, including major new policy actions to rapidly decarbonise electricity and transport sectors in the near term, the setting of clear short-term targets to guide the pathway to 2050, and significant reductions in the extraction of coal and gas due to significant demand drops.

Technology deployment and innovation

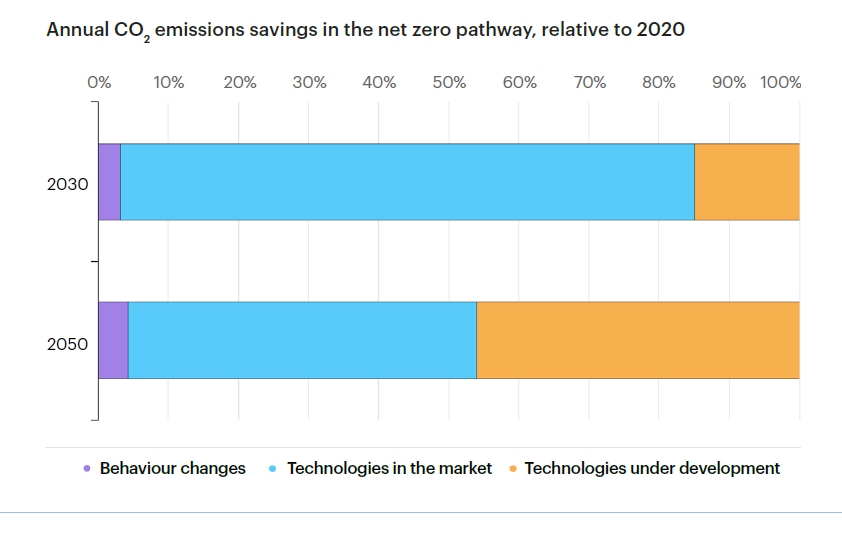

One of the peer reviewers on the report was Alan Finkel, former Chief Scientist and now “Special Advisor to the Australian Government on Low Emissions Technology”. A large proportion of the report focuses on new research and development required for ‘hard to decarbonise’ sectors, highlighting that nearly half of the reductions in emissions by 2050 come from technologies that are currently in the demonstration of prototype phase. This mirrors the Australian government’s focus on “technology roadmaps” instead of short-term deployment of clean energy technologies.

This finding may have informed comments made recently by US climate envoy John Kerry, who told BBC News that 50% of required emissions reductions will come from technologies ‘we don’t have yet’, but did not specify a source. However, the report also highlights at length that the vast majority of emissions reductions required prior to 2030, particularly in the power, transport and home heating sectors, can be done with technologies that are at a mature technological stage today.

“The biggest innovation needs concern advanced batteries, hydrogen electrolysers, and direct air capture and storage. Together, these three technology areas make vital contributions the reductions in CO2 emissions between 2030 and 2050 in our pathway”, write the IEA. But they also highlight that “Mandates and standards are vital to drive consumer spending and industry investment into the most efficient technologies. Targets and competitive auctions can enable wind and solar to accelerate the electricity sector transition. Fossil fuel subsidy phase-outs, carbon pricing and other market reforms can ensure appropriate price signals”.

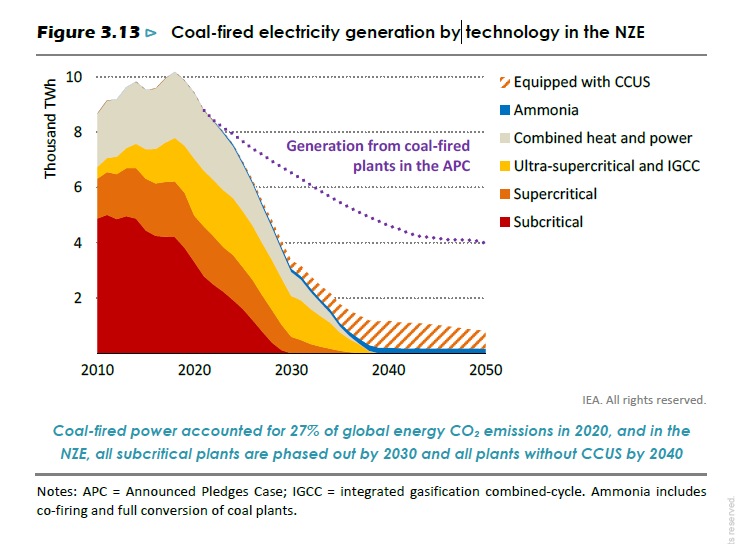

Australia’s government has, notoriously, shied away from short-term climate action. Unabated coal-fired power is only set to reach zero by around 2050 due to natural retirements, rather than 2030, as required for advanced economies in the IEA’s scenario. It has also refused to set mandates or targets for electric vehicles or heat pumps in gas fuelled homes – the IEA suggests in their report 60% of all global car sales ought to be electric by 2030.

International cooperation and short term targets needed for success

The IEA also highlights that significant global cooperation will be required to ensure that coherent measures that cross borders are implemented for a net zero by 2050 pathway. “Governments must work together in an elective and mutually beneficial manner to implement coherent measures that cross borders. This includes carefully managing domestic job creation and local commercial advantages with the collective global need for clean energy technology deployment”. Importantly, without greater levels of international cooperation, global CO2 emissions fall to zero just prior to 2090.

Australia’s government has been frequently seen as a drag on international climate policy and emissions reductions agreement, with the most recent being an effort to lobby for the inclusion of “carryover credits” at the 2019 COP25 conference.

Fossil gas producers – including Australia – will be hit hard in a net zero world

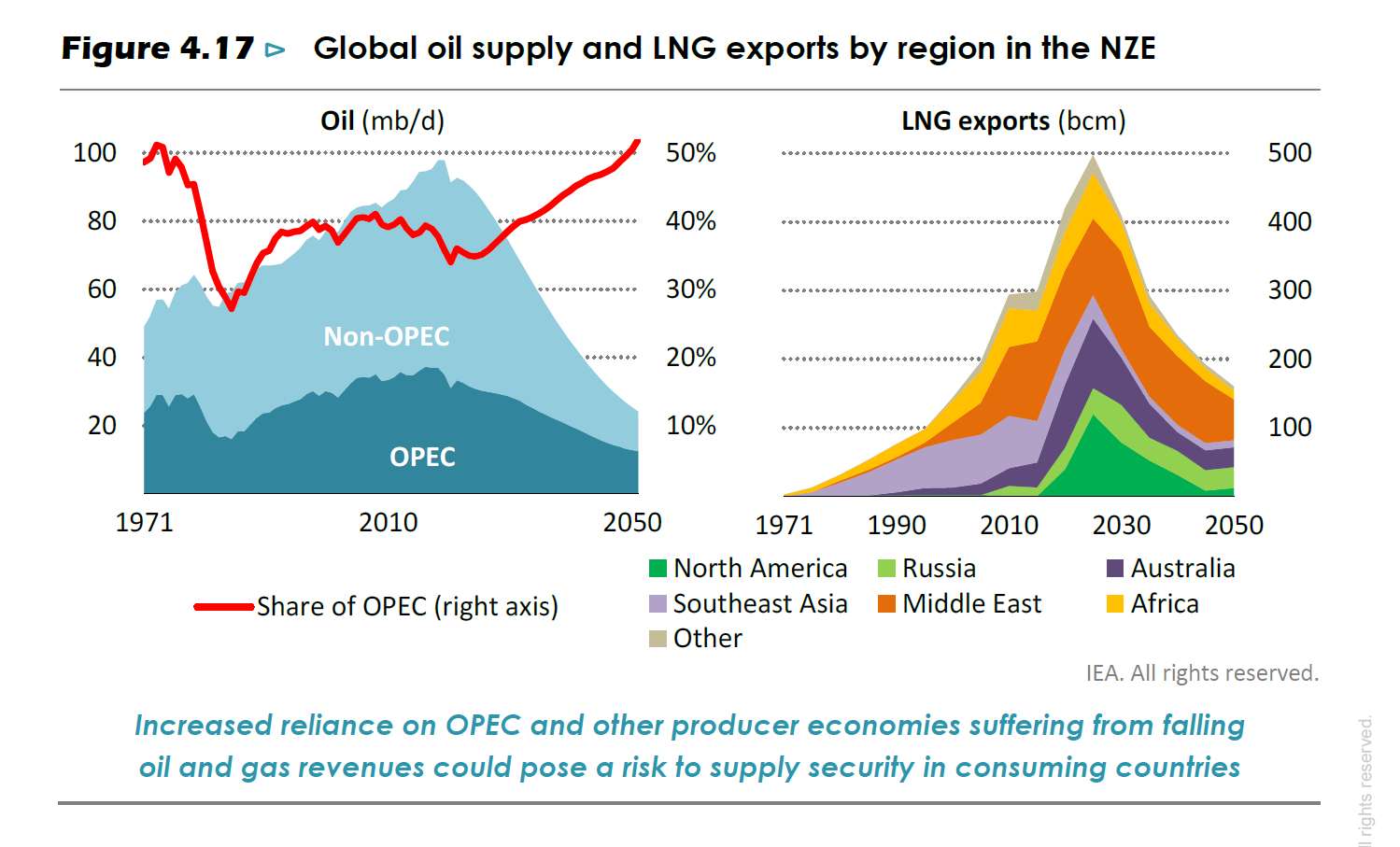

The report projects significant drops in demand for coal, oil and gas in the coming years, and highlights the impacts that this will have on economies that rely on revenue streams from these activities. “No new oil and natural gas fields are needed in our pathway”, write the IEA, suggesting the fall in demand for fossil fuels may create “knock-on societal effects” in key producing countries. From 2020 onwards, total investment in fossil gas supply is lower each subsequent decade.

Australia’s LNG exports fall from a high of approximately 90 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2020 to around 20 in 2050, though retains a larger share of remaining total in 2050 due to larger declines in production in the US. This outline of consistently decreasing LNG exports in Australia is directly counter to the government’s existing efforts to link COVID19 recovery to the burning, transport, extraction and sale of gas.

While fossil gas production peaks in the mid 2020s in the IEA’s scenario, coal is seen as well past its historical peak in the early 2010s, and decline precipitously in the short term. Both coal and gas comprise a sizeable proportion of Australia’s total export revenue, and there are no current plants from Australia’s current or opposition governments to plan in detail for the rapid winding down of these industries. “Retraining and regional revitalisation programmes would be essential to reduce the social impact of job losses at the local level and to enable workers and communities to find alternative livelihoods”, write the IEA, of coal mining shifts.

While fossil gas production peaks in the mid 2020s in the IEA’s scenario, coal is seen as well past its historical peak in the early 2010s, and decline precipitously in the short term. Both coal and gas comprise a sizeable proportion of Australia’s total export revenue, and there are no current plants from Australia’s current or opposition governments to plan in detail for the rapid winding down of these industries. “Retraining and regional revitalisation programmes would be essential to reduce the social impact of job losses at the local level and to enable workers and communities to find alternative livelihoods”, write the IEA, of coal mining shifts.

However, the IEA also highlight the possibility that new investments in mining for critical minerals used in the energy transition could fill the gaps.